The intersecting calls of the muezzins pierce the sweltering equatorial air as Ahmad Abdurrahman, imam of Narathiwat's central mosque, arrives on a racketing and underpowered moped to lead the noon prayer. "We're 80 percent Muslim here," he says, with an engaging smile.

Climb to the top of the minaret of Abdurrahman's modern, almost futuristic, mosque and he will show you a stunning view: palm-fringed beaches running along the South China Sea, wooden fishing boats moored in jostling huddles in the creek and lush plantations of oil palms and rubber trees that stretch to a mountainous horizon.

This is Thailand, and it looks like paradise - complete with a serpent named poverty.

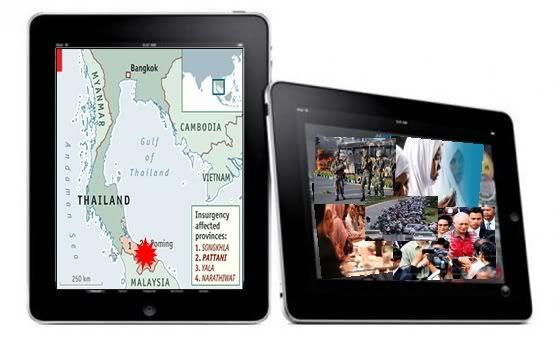

Economic growth, however robust, has a hard time eradicating the country's rural poverty and urban squalor, particularly here in Thailand's deep south. Narathiwat is only 840 kilometers (520 miles) as the crow flies from the capital Bangkok - but it might as well lie in another country in terms of race, religion, culture and even language.

"The Muslims are the poorest people in Thailand," imam Ahmad says. "We need government assistance." Eighty kilometers (50 miles) to the northwest, Chamnong Koomrak, governor of Pattani province, replies, "We're trying.... Our budget is growing by 10 percent a year. We give special privileges to Muslims to enter university and we want to develop the south, in fisheries, food-processing and tourism."

The truth is that there are few shortcuts to development anywhere. Both the government in Bangkok and the Muslim electorate in Thailand's southern provinces of Pattani, Satun, Narathiwat and Yala know that the key to prosperity is education. For the authorities, that means instruction in the Thai language. The people of the south agree - but they intend at the same time to preserve their religion and their culture.

The result is a fascinating renaissance of Muslim awareness spreading across the narrow, elongated arm of land that reaches down from the body of Buddhist Thailand in the north to the Muslim nation of Malaysia in the south. You see it every where, from the simple yet elegant central mosque in Pattani to the corrugated-iron mosques of the fishing villages along the eastern coast. You see it, too, among the 1,700 students who cram the classrooms of Narathiwat's Islamic Foundation for Education, built 20 years ago with a donation from the late King Faysal of Saudi Arabia. And you sense it in the faces of the tiny children learning Arabic from Jitsom bint Salih in a one-room madrasa, or Qur'anic school, in the sand-swept coastal hamlet of Ban Budi.

So who are these Thai Muslims? To government statisticians they are one of Thailand's minorities, perhaps four percent of a population now numbering about 55 million, overwhelmingly concentrated in the far south. To their Buddhist compatriots they are known as khaek, a word that means "visitor" in the Thai language - though the Muslims came to the region several centuries before the Thais.

To any real visitor, however - afarang or foreigner from overseas - the ethnic identity of the Muslims is obvious: They are Malay, just like their neighbors and relatives in the northern Malaysian states of Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu and Perlis. The two groups dress the same way: patterned sarong and white skullcap or angular black songkok hat for the men, long-sleeved dress and dawa head-scarf for the women. They speak the same Malay language, although many of the fishing families have a dialect all their own. And, most of all, they worship God in the same way, recoiling from the ornamented figures of Buddhism, Thailand's state religion. The fact that they bear Thai, not Malaysian, citizenship has nothing to do with cultural affinity - but it has everything to do with the politics of the past.

The Malays originated on the island of Borneo, now divided between Malaysia's Sabah and Sarawak and Indonesia's Kalimantan. About 1,500 years ago they began an expansion that took them south and west through the islands of Indonesia and northward to the Philippines and the Malay Peninsula. Meanwhile, the Thais - originating perhaps in southeastern China - were expanding southward in competition with peoples like the Shans, Mons and the Khmers of today's Kampuchea. The inevitable meeting of Thai and Malay came around the beginning of the 13th century.

But this meeting was not a clash of nations in any modern sense. Southeast Asia nearly 800 years ago was a shifting patchwork of kingdoms, each vying for tribute and influence but not necessarily for conquest. The Siamese, as the Thais used to be known, had one kingdom - but so did the Khmers, while to the south there were the kingdoms of Majahapit and Langchia. Just as the medieval Arab historian Ibn Khaldun theorized, when a state was vigorous, it expanded in territory and influence at the expense of weaker states - until the weak in turn became strong and led a fresh cycle of change.

Today's Muslim provinces of southern Thailand are the descendants of Malay kingdoms that in the Middle Ages paid tribute - in the form of bunga mas, or ornamental flowers of gold and silver - to the king of Siam. The payment of flowers showed a degree of loyalty to the king, and dependence on his protection against rival forces. It hardly mattered that the Siamese were purveyors of the region's Buddhist and Hindu tradition, while the Malays were 14th-century converts to Islam. What was at stake was power, not culture.

Yet it is the cultural difference between Thailand's Buddhist majority and Muslim minority that has imbued the south with its distinct flavor. This has survived the centuries, from the days when flowers were given as tribute to the modern era of representation - by a handful of Muslim deputies - in Thailand's National Assembly in Bangkok.

The mosque and the pondok, a religious boarding school for young Muslims, were the reason the culture survived. They still are, though the pondok is fast disappearing in favor of the madrasa, which receives government help in return for teaching secular subjects, including the Thai language, alongside the religious curriculum.

Turn off the main highway between Pattani and Narathiwat, go a kilometer or so along a mud road between glistening, luminous-green rice paddies, and you come to the Telok Manok mosque, built more than 300 years ago. Only a small minaret reminds you of Islam's Arabian origins; otherwise, the building, with walls and floor of heavy wood and roof of small, scalloped red tiles, is more reminiscent of an Indonesian longhouse.

The Telok Manok mosque is part of an Islamic tradition that remains real for almost all Thai Muslims. Late on a rainswept afternoon, we met young men there who were making a form of pilgrimage to the region's oldest mosque. Muhammad Said and Muhammad Hashim had both come from their homes in the Malaysian state of Perak. They were visiting their Thai friends, Muhammad Bidi Talodin and his cousin Ramli Talodin. We conversed in neither Thai nor Malay but in Arabic: Muhammad Bidi learned the language as a student in Benghazi, Libya, and 30-year-old Ramli had spent four years in Kuwait and six in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where he graduated with a degree in education. Now he teaches at the Islamic Foundation school in Narathiwat, keeping both tradition and culture alive.

Ramli and his colleagues use Arabic, as well as Malay, to promote the faith and its teachings. That may seem obvious: All good Muslims are supposed to be able to read the Qur'an in Arabic. But contrast it with Malaysia: In that country, where Islam is the state religion, most people now have difficulty reading the jawi, or Arabic, script because the written Malay language has been romanized. The Muslims of Thailand, however, invariably use the Arabic script when writing their language, be it in the mosque or outside.

For preserving and strengthening the use of Arabic, the Muslims of Thailand can thank their brethren in the Arab world. Since the mid-1970's, the countries of the Arabian Peninsula - especially Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar - have offered scholarships to Thai Muslims to pursue both religious and secular studies in the Middle East. Though there are only about half a dozen scholarships a year to any one country, their impact is enormous. Few Thai Muslims speak the national language well enough to enter a Thai university, so the chance to pursue advanced studies in an Arab country is a real boon. At the Narathiwat school, over 50 of the staff are graduates of universities in the Arab world. Fuad Tayyib, now aged 30, studied mathematics at Riyadh University; Nasir al-Din Hamid majored in Islamic studies in Kuwait; Hassan Hajj Ahmad is an alumnus of a high school in Kuwait and of the University of Qatar.

And there is even a chance to go to the most famous center of Islamic learning, al-Azhar University in Cairo. 'Umar Tayyib, the director of the Narathiwat school, says proudly, "Next year we should have three students at al-Azhar." And when they return? Naturally they will pass on their learning, just like the Narathiwat imam, Ahmad Abdurrahman. He went to Makkah to live at the age of 10 - "because my father was a shaykh in the mosque and wanted me to study Islam" - and then studied at al-Azhar in the 1960's and 1970's.

By now, enough students have returned from the Arab world to constitute a nucleus of Arabic-language teacher training in Thailand itself. Jitsom bint Salih, for example, teaches the children of her poor fishing village the Arabic that she learned not in the Middle East but in the Islamic Institute in Pattani - and the slogan on the wall of her tiny schoolroom proclaims in Arabic, "Teach the people what they do not know."

But we are leaping over the centuries. What happened between the days of bunga mas and the modern era? The answer is two-fold: First, Islam grew deep roots in the region; and second, the European powers arrived in Southeast Asia. Both factors were troublesome complications for successive Siamese monarchs.

Islam arrived in the wake of commerce. Muslim traders from the Middle East and India brought their religion with them as they sailed to Southeast Asia in search of spices and other riches. By the early 17th century Pattani had established itself as the center of Islamic learning in the Malay Peninsula. For the next 200 years and more Pattani produced scholars who not only translated Arabic texts for Malay readers but who also wrote their own religious works. Daud ibn Abdullah ibn Idris al-Fatani, for example, was a theologian whose expertise in fiqh, or jurisprudence, was recognized even in Makkah.

But the stronger Islam became in the region, the more its adherents identified not with the distant king of Siam but with their coreligionists in the Malay states to the south. The result was a series of uprisings, encouraged in part by the insensitivity of the Siamese bureaucrats to Muslim custom. By 1890 a Muslim writer described the officials who came to diminish the power of the traditional rulers and of the 'ulama, the religious leaders who advised them, as "the leeches and parasites of the state."

Such tensions, leading at one point to the exile of the ruler of Pattani, also reflected international conflicts. By the 16th century, Europe's colonial powers were competing for the land and resources of Southeast Asia. At first, the Siamese were pressed to grant trading concessions - to the Dutch, for example, giving them a monopoly over part of the country's external trade, and to the Portuguese to trade with certain Malay states. But soon Siam's independence was at stake. The French were approaching from their new domain in Laos and other parts of Indochina; the British were threatening to encroach both from India in the west and from Singapore and the Malay Peninsula in the souths.

By the beginning of this century the reformer King Chulalongkorn desperately needed some formula to stop his domain being nibbled away by the rival ambitions of the French, British, Russians, Germans and even Turks. The answer was the Anglo-Siamese Agreement of 1909: The King formally ceded tributary rights to four of Siam's southernmost Muslim provinces - Kedah, Terengganu, Kelantan and Perlis - to Britain in exchange for Britain's recognition of Siamese sovereignty over Pattani and the principalities surrounding it. It was a clever move for both parties: By sacrificing part of their traditional authority, the Siamese won the implicit protection of the British, who for their part could enjoy the plantation riches of northern Malaya while keeping Siam as a neutral buffer state between British India and French Indochina.

The only problem was that the agreement left many Muslims north of the new border to co-exist with a Buddhist majority with which they had little mutual sympathy. This juxtaposition led to the emergence, in the last 40 years, of various movements seeking Muslim independence from Thai rule.

Fortunately, governments can learn from their mistakes, and King Chulalongkorn's conciliatory instructions to his ministers three-quarters of a century ago have been recalled: "We regard [Islam] as a religion for those people in that part of the country." Muslim wishes have been heard and Muslims' circumstances have improved. Each Muslim province now has a central mosque built with government funds - to the tune of $1 million in the case of Ahmad Abdurrahman's mosque in Narathiwat. In Pattani, Governor Chamnong says, "Everyone is free to worship in his own way - but we want every Muslim to speak Thai. They are people of this country, and Thai is the official language." But that does not have to mean losing the culture of Islam, the governor adds: "We're trying to open a new faculty at the university in Islamic studies, so that the people don't have to go to Cairo."

In the meantime, life in the southern provinces goes on with the relaxed rhythm imposed by nature. Take away the small businessmen of Hatyai, Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat and most of Thailand's Muslims are rice farmers, plantation workers or fishermen. Life is hard, but simple. From fishing villages like Panare scores, even hundreds, of kolae fishing boats go out with the tide each day. Their steep, pointed prows are a mass of intricately painted curls; sterns and sides often bear beautiful paintings of Alpine scenes that none of the fishermen will ever see in real life. In the fields, the farmers and their families toil over the rice plants.

To the visiting farang, the scenes are a delightful passport to an era urbanized man has left behind. For the Thai Muslims entertainment is still a communal enjoyment. The fishing families huddle around a shared television. In villages like Chana, the inhabitants gather in the early morning to raise dozens of caged doves aloft on six-meter (20-foot) metal poles. The doves burst into songs that are judged for pitch, melody and volume. An outsider can hardly tell even from which direction the dove song is coming - but the owners can, and a bird that wins a major competition can end up being worth $12,000.

Will it stay this way forever? Perhaps not. Development, although slow, will bring cars to replace the ubiquitous mopeds. The potential of the valuable tin deposits in the hills is bound to force change. Fishermen will leave the dangers of the sea for easier jobs in the small factories now sprouting on the outskirts of Hatyai and Yala. Families may decide that watching the new television set carries more immediate interest than teaching a dove to sing.

But one thing seems certain to survive, and even grow: the interest in Islam. At the central mosque in Pattani businessman Abdullah Abdulwahab says, "Islam is getting stronger. Every mosque has a place to teach Islamic studies, and 40 percent of the people send their children to these schools. Each year, 1,000 people from the Pattani area do the Hajj. I did it three years ago, and I think I'll do it again." His confidence is surely right. Pattani, like the rest of southern Thailand, is leaving the era of the moped. Taking part in the noon prayer when we visited Pattani was a man with lettering on the back of his overalls. It said, "Chief Mechanic, Toyota, Pattani."

Written by John Andrews

Photographed by Nik Wheeler