In her customary birthday-eve address last Thursday, Thailand's Queen Sirikit told prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra one of her top concerns was the ongoing violence in the south. Ms Yingluck has proposed a similar degree of autonomy for the region as in Bangkok and Pattaya, which elect their governors. In other provinces, governors are appointed by Bangkok. But army chief general Prayuth Chan-ocha has publicly called the idea ''premature.''

Talks in various regional capitals between a government backed delegation and representatives of southern Malay Muslim insurgent groups, are paused because of the change of guard in Bangkok.

But analysts say the only way forward is to continue to talk, despite the apparent lack of breakthroughs.

Chulalongkorn University professor of political science Panitan Wattanayagorn, until recently spokesman for former premier Abhisit Vejjajiva who backed the talks, said the new government ‘’should maintain some level of communication to increase trust and confidence.’’

‘’Any discontinuation would not be good for the long term future.’’

Kasturi Mahkota, usually based in Sweden and representing the Pattani United Liberation Front (PULO), who has been a part of the talks, told The Straits Times ‘’We are waiting for a signal from the Yingluck government.’’

Thailand's Narathiwat province has seen two violent prison riots in three months - the latest on Thursday.

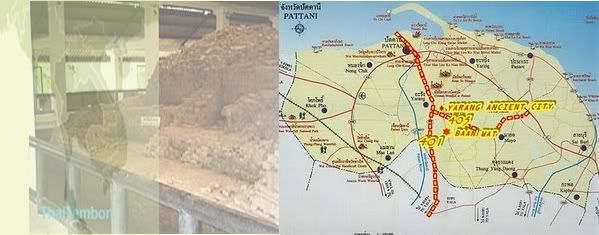

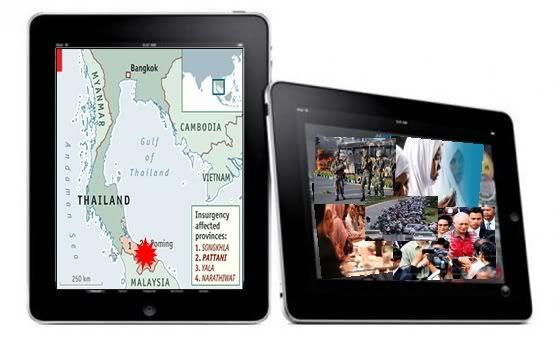

Almost daily roadside bombs and ambushes mainly targeted at security forces, and symbols and collaborators of the Thai state - official and civilians including monks - continue to puncture the peace in the Narathiwat, Yala and Pattani.

Security forces strike back with raids and detentions - and occasionally torture. Muslim religious figures are often targets. The militarization of the region is evident from roadblocks, armed patrols, and army camps surrounded by razor wire and sandbags.

The death toll after just seven years of the current cycle of violence stands at well over 4,500 - more than all those killed in 30 years of conflict between the United Kingdom and northern Ireland's Irish Republican Army.

Some 30-40 per cent of the violent incidents may be due to personal and criminal conflicts and vendettas; the region is also awash with guns in the hands of militias and criminals, and tit for tat killings are almost commonplace.

The ongoing violence shows that while the Thai army has contained the militant insurgency to a degree, separatists have increased levels of professionalism and continue to recruit, noted Anthony Davis this month in Jane's Intelligence Review.

Davis noted that ‘’on average nearly 50 people were killed and 75 injured every month over the first half of 2011 in violent incidents in the region, adding to a toll that has exceeded 4,600 dead and 7,000 wounded since January 2004.’’

‘’The underground separatist community has not merely survived but adapted and matured, while developing new skill sets and levels of competence.’’

There remains a wide gulf between the view of the conflict from Bangkok, and that of the Malay Muslims in the south.

‘’The southern Thai conflict is a war over legitimacy’’ professor Duncan McCargo of the UK's Leeds University wrote in his 2009 book ''Tearing Apart the Land.''

‘’For significant numbers of Patani Malays, Thai rule over their region has long lacked legitimacy.’’

‘’Substantive autonomy - probably called something else - is probably the only long-term solution that might satisfy most parties to the conflict.’’

Through the lens of the Bangkok establishment, autonomy opens the door to independence. On a recent day visit to the south after the election, when he was still foreign minister, Mr Kasit Piromya who now sits in parliament as part of the opposition, wondered aloud at the nature of the grievances of Malay Muslims.

He pointed out - correctly - that the Muslim population had complete religious and cultural freedom. But he made no mention of the issue of justice, and said talk of autonomy would stall any negotiations at the gate.

Separately, a mid-level ministry of foreign affairs official insisted that militants constituted only a small minority. Yet she was unable to explain how a small minority could survive without popular sympathy, if not active support.

‘’That is typical of Bangkok’’ said Don Pathan, a prominent Thai journalist based in Yala. ‘’But Malay Muslims have their own narrative, their own heroes.’’

But even Mr Kasit said there was no option but to continue dialogue.

Each side, however, needs to offer a concession. The insurgent representatives need to show the militants they have the clout to wrest a concession. And the Thai state wants proof that the men in the talks can call a halt to attacks - something that is not entirely clear.

While there have been small signs of progress in the south, much more has remained unchanged. Rights activist Pornpen Khongkachonkiet of the independent Cross Cultural Foundation which is active in the south, in an interview said ‘’I am doing the same thing I was doing five years ago. I'm looking for details of three detainees. I'm trying to find out where they are. Two have been missing for three months.’’

However, that talks have been taking place at all - involving Thailand's National Security Council and a senior army general - is a good sign, said an analyst who is closely following the process.

‘’Mountains have moved’’ he said. ‘’If you compare where we are to two years ago, it is extraordinary.’’

‘’The government has made tremendous progress in engaging with insurgent groups in open-ended dialogue which has official status, with the army involved, and the army chief kept informed.’’

Recently a group of civil society representatives, both Buddhists and Muslims, also held talks with representatives of insurgency groups outside Thailand.

Noted Anthony Davis : ‘’In a break with traditional mindsets, both insurgent representatives and the National Security Council.. have separately conceded that the role of civil society will be central in formulating solutions to the conflict.’’